A new page to check out: “Sisterhood of Motherhood”. A couple of poems devoted to the beautiful and challenging process of becoming a mother. Enjoy! – MGB

Author Archives: Mary Grace Bertulfo

Koan #3: Oil Spill on the Des Plaines

65,000 gallons on land.

“The oil spill has been contained,”

an official-sounding man from Caterpillar

chirped brightly on NPR’s morning newscast.

No more wildlife will be affected —

beyond the ones already touched.

6,000 gallons of oil

sludged into the Des Plaines River.

How many blue gills?

How many herons?

How many egrets?

How many frogs?

How many salamanders and newts?

How many beavers, raccoons, button bushes?

No need to worry, officials assure us.

It was already an Industrial Zone anyway.

Koan #2: Last Shudder before Spring

Flat white Great Lakes sky,

Distant frozen fog,

Yet warm enough

for hammers

to sound on rooftops.

Men work in hooded sweatshirts,

jeans, thin tennis shoes

upon brick bungalows

that kept us warm

in the bleak months.

But the trees

stand haggard,

bare-limbed and stoic.

Maple and oak and Kentucky buckeyes –

indistinguishable to my eyes.

All stand equally stripped,

naked, vulnerable

in the diminishing chill.

Oh, how they stretch

their feathery twig tips

towards the hiding sun!

How can I not cheer

for their survival?

No one calls Chicago trees heroes,

but they are.

Even we hearty people,

blood winter-thickened,

cozy up inside our walled homes.

Our windows may rattle

beside the El tracks,

but still, we are warm.

Chicago’s winter trees

brave ice storms,

branches snapped

by unflinching winds,

endure the bitter bite

of Below Zero.

Water-stained, whorled, gnarled

gray on brown bark –

they stand and endure.

In 40 degree air,

my hands gloveless,

the skin on my fingers redden,

knuckles chafed and aggravated.

Nowhere near Below Zero.

Koan #1: Life Hungry

Perched securely on a branch

above my car,

the Cooper’s hawk

munched on young pigeon.

Starlings scattered,

downy feathers

drifted like summertime snow

upon my head.

Zen Flesh, Zen Bones

A tattered yellow book, ZEN FLESH, ZEN BONES sold for 50 cents at a used book store. Thin, old tape hangs the front cover onto the manuscript’s body; the back cover is lost to moves from Los Angeles to Berkeley to Chicago. Inside, over 100 stories and problems and ancient teachings from 5 centuries of Chinese and Japanese monks. Fun stories. Confusing stories. Stories that stick to me and make me breathe more slowly, with more appreciation of the world around me.

I’ve hiked the hills of Berkeley in California seeking solace, meditated the sand blowing across the ocher and limestone faces of dry desert cliffs at Red Rocks in Nevada, and stood in the glory of woods in Chicago where the low Fall sun slanted through golden maple leaves. What does it take to feel alive? To grasp the moment that is now, the dazzling mystery of the world we are in?

Somehow, we are lost. Rich as we have become as a nation, brilliant as we are with technological advances, as far as we’ve gone to explore space, still, we are lost. In our busy-ness, in my busy-ness…lost. Loving as we are, well-meaning as we are, we can lose ourselves; striving as we do just to make ends meet, we forget how deep beauty really is.

And it is deep.

So. This thread, KOAN OF THE WILD, is a play on the phrase “Call of the Wild”. A few observations, a kind of poetic puzzle. Writers know that words are poor substitutes for the real deal, for the actual EXPERIENCE of living. But here’s my humble attempt, anyhow. Poetry in the service of Nature.

An offering: Moments connecting with the Wilderness that is our World; moments that have taken my breath away. Sometimes, all it takes for me to feel the alive-ness of being alive is for me to run to the woods, the scent of loam and leaves on the river caught in the wind.

Sliding Bracelets

In the 16th century Philippines, Visayans had ingeniously divided the day into hours based on events like: Iguritlogna, the time that hens lay eggs. Or Natupongna sa lubi, the time when the sun descends into the palm trees. My favorite is Makalululu, the hour when you point to the sun and your bracelets slide down your arm. Bracelet-sliding time. It even sounds poetic.

We can chop time into precise numerical abstractions – seconds, minutes, hours. Or map it onto the phases of the moon. We can mark it by the body’s life cycle – birth, walking upright, a girl’s first menses, the fruitful swelling of her womb. We can mark time by ritual rite of passage — circumcision to signal a covenant with God or a bar mitzvah when a boy reads his Torah portion and becomes a man. Eras, epochs, ages, decades, centenials. However we do it, we human beings gage our own time.

Imagine: gold bangles rest on your wrists. The slow rise of your hand as you point to the sun. The faint tinkle of gold as ten bracelets slide cool, smooth, down to your elbows. Makalululu, the Hour of Sliding Bracelets.

I reserve this thread, this space on my blog for pondering time, savoring the wild romp and process of writing stories that transport us to past ages and the distant shores of memory.

Time. History. Writing. Reading. Ahhhhh. *contented sigh*

Welcome to the passages of skin and gold.

Kadaugan, Part V: The Performance

If you read the last posting (Kadaugan, Part IV), you’ll know that I started out at the Kadaugan sa Mactan getting stuck in a poor spot, 3 rows of people behind a fence that separates the audience from the Re-enactment of the Battle of Mactan on the shores of Magellan Bay. And, with a bit of luck, I was able to garner a Press Pass to get the behind the scenes glimpse — or, in this case, on-shore.

And glimpse I did. Here is a taste of what I saw. The performance was choreographed and directed. (I still have to look up the director’s name; it sounded to me like Rogi Palanca.) I’ve divided the performance into scenes or acts, as I interpreted them:

Setting and Venue

9 a.m., Saturday April 27th. Four-hundred-and-eighty-six years after the actual Battle of Mactan. The Bay of Magellan. An overcast day. The sun shined behind the clouds. The bay itself: a small crescent moon of fine sand, green silty waters, and three strands of mangroves.

Pre-show Preparations

Prior to the show, there was singing and prayers beneath the mural of the Battle. The Philippine national flag was raised. There was a a gun salute. The mayor and a congresswoman walked an offering of flowers to the statue of Lapu-lapu which towers over the Bay.

Then, on-shore, re-enactors practice their moves. Men dressed as Lapu-lapu’s warriors twirl 8 foot spears and wield mock-kampilans. Women milled about talking about the daily work dressed in sixteenth century-ish clothes. (For modesty’s sake, both women and men are dressed in modified costumes. Traditional sixteenth century clothing was very scant by today’s standards. And, also, in reality this was a pre-Christian society which did not have the same social prescriptions. Another way to look at it is that they were much more comfortable with their bodies. Also, some Friars viewed Visayan tattoos as art that garmented the skin.) In present day Mactan, the audience buzzed with anticipation.

Music heightens the tension and anticipation. It’s a mix of traditional instruments, percussions, and modern melodies. Very dramatic.

Entrance of mga Artista, the Actors.

The MC announced the arrival of the artista, the two young Filipino movie stars who played Magellan and Lapu-lapu. Cries and gasps rose up whenever the two men moved through the crowd.

—

Act 1: The Barangay and the Ceremony

Quiet in the barangay. Women in long skirts carry baskets they dip in the sea, perhaps catching fish, perhaps washing. Men wade in the water hunting for fish with spears. A troop of boys dressed in white arrive with dried rushes or switches, dancing. Then, a troop of young women arrive with baskets of leaves and offerings upon their heads. They step in time to drums; bells wind around their ankles. Two women in purple, presumably babaylan (women shamans), enter the dance. Musicians in purple play gorgeous percussions like kolatong, a long bamboo drum.

Act 2: The Parlay

Magellan’s priest and two or three of his conquistadors arrive on the shores of the Bay. They parlay with Lapu-lapu’s officer, a large, imposing Mactanyo (still no tilde!). The parlay takes the form of mime and gestures: grand, sweeping motions of the arms. The meaning seems clear. Lapu-lapu’s official waves the priest and conquistadors away, then turns to LL who nods his ascent. Magellan’s priest and conquistadors stay. This time, Lapu-lapu himself motions for them to layas, begone. The party leaves huffily, with dramatic flair.

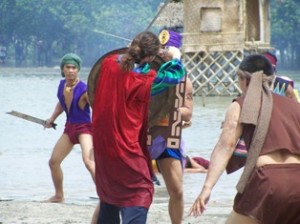

Act 3: The Battle

Magellan’s conquistadors line up in the sea. Lapu-lapu’s warriors line up on the shore. They stare each other down across the water, then begin to charge at one another. The battle ensues. Swords clash, men fall seemingly dead upon the sand. Women and children run screaming in the backdrop. Canons sound — and the roofs of two nipa houses catch on fire. Meanwhile, Lapu-lapu stands on a far pier, watching the scene. Magellan hangs back, doing the same.

Act 4: Lapu-lapu versus Magellan

Magellan comes forward. Lapu-lapu and he engage each other. They circle and parry, dodge and hit. Lapu-lapu  pierces Magellan, near the middle. Magellan is felled. A great cry of triumph issues from the remainder of Lapu-lapu’s men. LL’s men begin to gather the dead. Some six or so men hoist Magellan’s fallen body up and carry it away. Other men gather the dead and carefully place the Spanish soldiers next to each other in the center of shore. Lapu-lapu’s wounded are walked back by other kababayan. This was actually very moving because it seemed that great tenderness was taken with all who fell. I was left with a sense of the loss on both sides and the sadness that is inevitable with battles.

pierces Magellan, near the middle. Magellan is felled. A great cry of triumph issues from the remainder of Lapu-lapu’s men. LL’s men begin to gather the dead. Some six or so men hoist Magellan’s fallen body up and carry it away. Other men gather the dead and carefully place the Spanish soldiers next to each other in the center of shore. Lapu-lapu’s wounded are walked back by other kababayan. This was actually very moving because it seemed that great tenderness was taken with all who fell. I was left with a sense of the loss on both sides and the sadness that is inevitable with battles.

Act 5: Home, Again

Lapu-lapu returns home. A carnival atmosphere. The performance ends with the two dance troops of young men and women returning and all — the datus, the babaylan, the families — dance and parade up onto the pier and back down the shore.

Kadaugan, Part IV: Adventures Behind the Scenes

We left the hotel this morning at 7 a.m. and caught a taxi out 11 kilometers to the Mactan Shrine where there  are two monuments, one is a marker of the place where Magellan fell in battle. And the other marker is for Lapu-lapu. Every year, they re-enact the Battle of Mactan. This year was the 486th.

are two monuments, one is a marker of the place where Magellan fell in battle. And the other marker is for Lapu-lapu. Every year, they re-enact the Battle of Mactan. This year was the 486th.

We arrived and there was a cavalcade of police piled in open-backed trucks. Guards with rifles milled in and out of the crowds. This is how we knew it would be a big event. The bigger the event, the more heavily armed the security. On the side of the road, women sold sugared ube (purple yam) cookies, choco marbled rolls, and pan de sal (breakfast rolls). There were stalls with fans woven from nipa palm and men venders carrying plastic crates of ice-cold water slung from their shoulders. There were young green mangoes, fingerling bananas hanging from corrugated tin roof stalls, and chickens pecking around in yards. The local neighborhood watched us with half-amused smiles; we were such a bizarre spectacle traipsing through their neighborhood of sari-sari stores and homes.

There were a few hundred families at the Kadaugan Festival. I didn’t take a head-count so I couldn’t say. But if I had to guess, there were something like 500-ish people there. Before the festivities, the event began with singing and prayers. I found this very moving, especially in light of Filipino historical traditions. In the old days, in the sixteenth century, every major community event — like harvests or battles — began with prayers and offerings. There were beautifully gorgeous and simple songs accompanied by acoustic guitar.

The Tourism Officer I spoke to on the phone two days before suggested that we arrive a couple of hours early to try and get a good puwesto, a good spot for viewing the Re-enactment. I had many plans of taking crystal clear, unobstructed photos. But, by the time we figured out where to stand, the best spots had filled up two or three people deep. It was going to be really hard to see any of the performance.

I guess I should explain that the Re-enactment happens on the shores of what is now known as Magellan Bay. The opening is enclosed by 3 strands of mangroves on one side and on the opposite side is the shore. The shore, small and crescent-moon shaped served as the stage. Just behind the shore was a concrete, iron-fenced area. It is in this area that most of us thronging to see the spectacle stood. The re-enactors stood on the shore, separated from the throng of us by the fence. Through the iron bars, you could see men in sixteenth century  garb, cloths wound around their waists, scarves about their heads. Many had kampilan, bamboo shields, and spears about two heads taller than themselves. We were all looking for Lapu-lapu and Magellan.

garb, cloths wound around their waists, scarves about their heads. Many had kampilan, bamboo shields, and spears about two heads taller than themselves. We were all looking for Lapu-lapu and Magellan.

I was a bit disappointed. There’d be no clear photos of the performance from this distance, standing behind 3 other people. So, I decided to go and ask someone if there was some better spot to stand in. Along the way, I noticed the huge statue of Lapu-lapu towering over the plaza. It was festooned with two huge wreaths of flowers and balloons tied every few feet around the perimeter. I saw a man who was talking to 3 of the Kadaugan staff (they had special tee-shirts on and badges around their necks). I asked him, “Nasaan po ang magandang puewesto para makita ang performance?”

He laughed, took a puff of his cigarette, fixed me with a cynical eye and replied, “Sa media booth.” In the media stands. He and his staff laughed at that. A lotta good this was gonna do me. “Media ka ba?” He asked me. Are you media? “Hindi,” I replied. No. I was there as a tourist, even though I was doing research for my book, I wasn’t on assignment (though, certainly with the right photos and my avid notes a great essay and article could come out of this experience). I had my digital camera draped around my neck. I had my black field bag. I had my very American looking clothes, my blue-eyed sweetie of a husband, and our mestizo-looking boy with us. We stuck out quite a bit from the crowd.

“Have you EVER been part of the media?” he asked me, giving me a second chance. At this point, I opened up my field bag and produced a reprint of one of my articles. It was glossy. It had my business card clipped to it. I had been carrying a stack of them around…well, just in case they’d come in handy for something. The man turned to his staff and told them to go find me a press pass. Now, at this point, if I had been on Candid Camera, I would have turned to it and mugged some kind of incredulous smile and whispered, “Can you believe this?!”

I pointed to Alan and Boy-boy and said, in Tagalog that I’m here with my family. I didn’t want to leave them. I’d dragged them up and down the East Coast of Cebu for 2 days already, in a van, through motion sickness and heat and humidity. They’d been such good sports already and so supportive of my work. This was the one thing I really wanted to make sure we all saw together. The man looked at them and said, “No, just you.” Because they weren’t media. So, I declined the pass. It just didn’t feel right to strand my family in that way. Then, a big wig wearing a formal barong Tagalog came up to the man. They began shaking hands and talking. And I knew I’d missed my chance to get behind the scenes.

I pointed to Alan and Boy-boy and said, in Tagalog that I’m here with my family. I didn’t want to leave them. I’d dragged them up and down the East Coast of Cebu for 2 days already, in a van, through motion sickness and heat and humidity. They’d been such good sports already and so supportive of my work. This was the one thing I really wanted to make sure we all saw together. The man looked at them and said, “No, just you.” Because they weren’t media. So, I declined the pass. It just didn’t feel right to strand my family in that way. Then, a big wig wearing a formal barong Tagalog came up to the man. They began shaking hands and talking. And I knew I’d missed my chance to get behind the scenes.

My family and I walked away, back towards the throng to find a spot. And we managed one, in a far corner, by some teachers. Alan turned to me and said, “You should’ve taken the Press Pass.” I said, “No. I want to be with my family. I want to be with you guys.”

“We would’ve been all right. We’re in a good spot, now.” And I looked at what we’d found as a puwesto. It was close to the VIP section (though still fenced off and far away from the shore). It was in the shade. It was pretty good, at least decently comfortable even if the photos would be too distant to be of use. And then I began to think about it.

“Go back,” Alan said. “Go tell him you changed your mind.”

“No,” I said, afraid to look foolish. “That would be ridiculous. I’d already turned him down.”

“Just ask. Look. We’re all right. See? This is for your work. So, go and do it,” Alan instructed. I looked at my Boy. He mumbled something to his dad like, “Isn’t that the whole point we’re here, for Mama’s work?” I don’t know why, but in that moment it felt like such a hard decision, one that working mothers have to face all the time. When to stay and when to go. I also felt this wonderful sense that it was a good thing, something I’d be proud of that my son could see me at work and see the value of women working, doing things that aren’t strictly traditional.

“All right,” I said and sighed. “I guess I’ll go.” I still felt foolish. “All I can do is ask, right?”

At that very moment — I kid you not — the Man’s assistant showed up with a Press Pass dangling from a string necklace in his hand. He gave it to me and indicated for me to put it on. He waited. OMG! The timing was so brilliant!

I spent the rest of the morning following the Manila and Cebu press folks around. Me, this little writer from Chicago. And, in the end, the Man’s staff let Alan and Boy-boy in to sit with the VIP’s. Was it kindness or guile? Or a practical move? Or all of the above, to get more coverage of the event and spread the publicity? Probably all. And, man, am I thankful.

Kadaugan, Part III: War and Peace

When planning for this trip, I’d focused a lot on the Battle of Mactan. It’s what we Westerners tend to focus on in history: the battles, the wars. I’m not the first (and won’t be the last) to notice that we human beings seem to mark our epochs from one time of war to another. Even the word “Peacetime”, which my elders lived through, means the time after MacArthur, the time after WWII in the Philippines. Peace, often becomes synonymous with an absence of war, rather than a fertile and vibrant time that defines itself. What does the heart of peace look like? What IS actually a creative sense of PEACE? How is it lead from the Spirit?

So, when, a few days ago, I thought that I wouldn’t be able to attend the Re-enactment, it shocked me artistically. It made me realize how much I was depending upon the idea of this battle to define Filipino history. It’s a challenge to feel tossed at sea with no clear sense of the Story. But, like most things, I find that when I surrender to instinct, try and humble down and listen to what life has to teach, ultimately it leads to a deeper place.

When I thought I’d miss the Battle of Mactan Re-enactment, it forced me to rethink would I could see in its absence. And what I saw was this:

* The Santo Ninyo Basillica (still missing the tilde!).

* I saw elder women selling red candles before the open doors of the cathedral.

* I saw people praying for transformations in their lives.

* I saw very poor, hard-working tinderas at the side of the road selling Sto. Ninyos.

* I saw a country, rich in natural beauty, rich in family ties, rich in spirituality even as the politicians may struggle with corruption and a hard economy.

* Songs and dances in praise to God.

* Offerings to Diwata, Nature Spirits.

* Boys with their arms draped around each other in camaraderie.

* Old traditions of babaylans continuing, though much changed, today.

The Elder women here fascinate me. They are small and wiry, bronzed by the sun. Two things are persistent about them: Their powers of negotiation at the market stalls and their smiles, very humble and sincere. Theirs is not the strength of canons, but the enduring strength of palm trees. They are able to bend with the flow of wind current and survive.

Mosquito Scoreboard

In 1983 –> 17 mosquito bites. Mosquitoes declared winners.

In 1994 –> 14+ mosquito bites. Mosquitoes declared winners.

Now, 2007, the rematch:

20 April

Got here yesterday — zero mosquito bites!

Been up and out this morning — zero bites!

21 April – 26 April

After walking and taking jeepney all over Cebu City; being out on the coast; sleeping at Marine Sanctuary in Oslob — 3 mosquito bites.