That moment when you calculate the moon phases in 1521 and can now reckon time precisely in the world of your novel. Kilat-kilat, the time when the moon is a flash of lightning. Ah, twenty-first century tech meets the precolonial Philippines!

Category Archives: Visayas Research

Kadaugan, Part V: The Performance

If you read the last posting (Kadaugan, Part IV), you’ll know that I started out at the Kadaugan sa Mactan getting stuck in a poor spot, 3 rows of people behind a fence that separates the audience from the Re-enactment of the Battle of Mactan on the shores of Magellan Bay. And, with a bit of luck, I was able to garner a Press Pass to get the behind the scenes glimpse — or, in this case, on-shore.

And glimpse I did. Here is a taste of what I saw. The performance was choreographed and directed. (I still have to look up the director’s name; it sounded to me like Rogi Palanca.) I’ve divided the performance into scenes or acts, as I interpreted them:

Setting and Venue

9 a.m., Saturday April 27th. Four-hundred-and-eighty-six years after the actual Battle of Mactan. The Bay of Magellan. An overcast day. The sun shined behind the clouds. The bay itself: a small crescent moon of fine sand, green silty waters, and three strands of mangroves.

Pre-show Preparations

Prior to the show, there was singing and prayers beneath the mural of the Battle. The Philippine national flag was raised. There was a a gun salute. The mayor and a congresswoman walked an offering of flowers to the statue of Lapu-lapu which towers over the Bay.

Then, on-shore, re-enactors practice their moves. Men dressed as Lapu-lapu’s warriors twirl 8 foot spears and wield mock-kampilans. Women milled about talking about the daily work dressed in sixteenth century-ish clothes. (For modesty’s sake, both women and men are dressed in modified costumes. Traditional sixteenth century clothing was very scant by today’s standards. And, also, in reality this was a pre-Christian society which did not have the same social prescriptions. Another way to look at it is that they were much more comfortable with their bodies. Also, some Friars viewed Visayan tattoos as art that garmented the skin.) In present day Mactan, the audience buzzed with anticipation.

Music heightens the tension and anticipation. It’s a mix of traditional instruments, percussions, and modern melodies. Very dramatic.

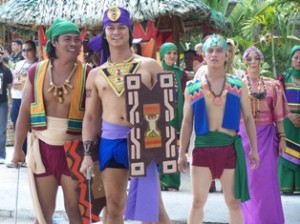

Entrance of mga Artista, the Actors.

The MC announced the arrival of the artista, the two young Filipino movie stars who played Magellan and Lapu-lapu. Cries and gasps rose up whenever the two men moved through the crowd.

—

Act 1: The Barangay and the Ceremony

Quiet in the barangay. Women in long skirts carry baskets they dip in the sea, perhaps catching fish, perhaps washing. Men wade in the water hunting for fish with spears. A troop of boys dressed in white arrive with dried rushes or switches, dancing. Then, a troop of young women arrive with baskets of leaves and offerings upon their heads. They step in time to drums; bells wind around their ankles. Two women in purple, presumably babaylan (women shamans), enter the dance. Musicians in purple play gorgeous percussions like kolatong, a long bamboo drum.

Act 2: The Parlay

Magellan’s priest and two or three of his conquistadors arrive on the shores of the Bay. They parlay with Lapu-lapu’s officer, a large, imposing Mactanyo (still no tilde!). The parlay takes the form of mime and gestures: grand, sweeping motions of the arms. The meaning seems clear. Lapu-lapu’s official waves the priest and conquistadors away, then turns to LL who nods his ascent. Magellan’s priest and conquistadors stay. This time, Lapu-lapu himself motions for them to layas, begone. The party leaves huffily, with dramatic flair.

Act 3: The Battle

Magellan’s conquistadors line up in the sea. Lapu-lapu’s warriors line up on the shore. They stare each other down across the water, then begin to charge at one another. The battle ensues. Swords clash, men fall seemingly dead upon the sand. Women and children run screaming in the backdrop. Canons sound — and the roofs of two nipa houses catch on fire. Meanwhile, Lapu-lapu stands on a far pier, watching the scene. Magellan hangs back, doing the same.

Act 4: Lapu-lapu versus Magellan

Magellan comes forward. Lapu-lapu and he engage each other. They circle and parry, dodge and hit. Lapu-lapu  pierces Magellan, near the middle. Magellan is felled. A great cry of triumph issues from the remainder of Lapu-lapu’s men. LL’s men begin to gather the dead. Some six or so men hoist Magellan’s fallen body up and carry it away. Other men gather the dead and carefully place the Spanish soldiers next to each other in the center of shore. Lapu-lapu’s wounded are walked back by other kababayan. This was actually very moving because it seemed that great tenderness was taken with all who fell. I was left with a sense of the loss on both sides and the sadness that is inevitable with battles.

pierces Magellan, near the middle. Magellan is felled. A great cry of triumph issues from the remainder of Lapu-lapu’s men. LL’s men begin to gather the dead. Some six or so men hoist Magellan’s fallen body up and carry it away. Other men gather the dead and carefully place the Spanish soldiers next to each other in the center of shore. Lapu-lapu’s wounded are walked back by other kababayan. This was actually very moving because it seemed that great tenderness was taken with all who fell. I was left with a sense of the loss on both sides and the sadness that is inevitable with battles.

Act 5: Home, Again

Lapu-lapu returns home. A carnival atmosphere. The performance ends with the two dance troops of young men and women returning and all — the datus, the babaylan, the families — dance and parade up onto the pier and back down the shore.

Kadaugan, Part IV: Adventures Behind the Scenes

We left the hotel this morning at 7 a.m. and caught a taxi out 11 kilometers to the Mactan Shrine where there  are two monuments, one is a marker of the place where Magellan fell in battle. And the other marker is for Lapu-lapu. Every year, they re-enact the Battle of Mactan. This year was the 486th.

are two monuments, one is a marker of the place where Magellan fell in battle. And the other marker is for Lapu-lapu. Every year, they re-enact the Battle of Mactan. This year was the 486th.

We arrived and there was a cavalcade of police piled in open-backed trucks. Guards with rifles milled in and out of the crowds. This is how we knew it would be a big event. The bigger the event, the more heavily armed the security. On the side of the road, women sold sugared ube (purple yam) cookies, choco marbled rolls, and pan de sal (breakfast rolls). There were stalls with fans woven from nipa palm and men venders carrying plastic crates of ice-cold water slung from their shoulders. There were young green mangoes, fingerling bananas hanging from corrugated tin roof stalls, and chickens pecking around in yards. The local neighborhood watched us with half-amused smiles; we were such a bizarre spectacle traipsing through their neighborhood of sari-sari stores and homes.

There were a few hundred families at the Kadaugan Festival. I didn’t take a head-count so I couldn’t say. But if I had to guess, there were something like 500-ish people there. Before the festivities, the event began with singing and prayers. I found this very moving, especially in light of Filipino historical traditions. In the old days, in the sixteenth century, every major community event — like harvests or battles — began with prayers and offerings. There were beautifully gorgeous and simple songs accompanied by acoustic guitar.

The Tourism Officer I spoke to on the phone two days before suggested that we arrive a couple of hours early to try and get a good puwesto, a good spot for viewing the Re-enactment. I had many plans of taking crystal clear, unobstructed photos. But, by the time we figured out where to stand, the best spots had filled up two or three people deep. It was going to be really hard to see any of the performance.

I guess I should explain that the Re-enactment happens on the shores of what is now known as Magellan Bay. The opening is enclosed by 3 strands of mangroves on one side and on the opposite side is the shore. The shore, small and crescent-moon shaped served as the stage. Just behind the shore was a concrete, iron-fenced area. It is in this area that most of us thronging to see the spectacle stood. The re-enactors stood on the shore, separated from the throng of us by the fence. Through the iron bars, you could see men in sixteenth century  garb, cloths wound around their waists, scarves about their heads. Many had kampilan, bamboo shields, and spears about two heads taller than themselves. We were all looking for Lapu-lapu and Magellan.

garb, cloths wound around their waists, scarves about their heads. Many had kampilan, bamboo shields, and spears about two heads taller than themselves. We were all looking for Lapu-lapu and Magellan.

I was a bit disappointed. There’d be no clear photos of the performance from this distance, standing behind 3 other people. So, I decided to go and ask someone if there was some better spot to stand in. Along the way, I noticed the huge statue of Lapu-lapu towering over the plaza. It was festooned with two huge wreaths of flowers and balloons tied every few feet around the perimeter. I saw a man who was talking to 3 of the Kadaugan staff (they had special tee-shirts on and badges around their necks). I asked him, “Nasaan po ang magandang puewesto para makita ang performance?”

He laughed, took a puff of his cigarette, fixed me with a cynical eye and replied, “Sa media booth.” In the media stands. He and his staff laughed at that. A lotta good this was gonna do me. “Media ka ba?” He asked me. Are you media? “Hindi,” I replied. No. I was there as a tourist, even though I was doing research for my book, I wasn’t on assignment (though, certainly with the right photos and my avid notes a great essay and article could come out of this experience). I had my digital camera draped around my neck. I had my black field bag. I had my very American looking clothes, my blue-eyed sweetie of a husband, and our mestizo-looking boy with us. We stuck out quite a bit from the crowd.

“Have you EVER been part of the media?” he asked me, giving me a second chance. At this point, I opened up my field bag and produced a reprint of one of my articles. It was glossy. It had my business card clipped to it. I had been carrying a stack of them around…well, just in case they’d come in handy for something. The man turned to his staff and told them to go find me a press pass. Now, at this point, if I had been on Candid Camera, I would have turned to it and mugged some kind of incredulous smile and whispered, “Can you believe this?!”

I pointed to Alan and Boy-boy and said, in Tagalog that I’m here with my family. I didn’t want to leave them. I’d dragged them up and down the East Coast of Cebu for 2 days already, in a van, through motion sickness and heat and humidity. They’d been such good sports already and so supportive of my work. This was the one thing I really wanted to make sure we all saw together. The man looked at them and said, “No, just you.” Because they weren’t media. So, I declined the pass. It just didn’t feel right to strand my family in that way. Then, a big wig wearing a formal barong Tagalog came up to the man. They began shaking hands and talking. And I knew I’d missed my chance to get behind the scenes.

I pointed to Alan and Boy-boy and said, in Tagalog that I’m here with my family. I didn’t want to leave them. I’d dragged them up and down the East Coast of Cebu for 2 days already, in a van, through motion sickness and heat and humidity. They’d been such good sports already and so supportive of my work. This was the one thing I really wanted to make sure we all saw together. The man looked at them and said, “No, just you.” Because they weren’t media. So, I declined the pass. It just didn’t feel right to strand my family in that way. Then, a big wig wearing a formal barong Tagalog came up to the man. They began shaking hands and talking. And I knew I’d missed my chance to get behind the scenes.

My family and I walked away, back towards the throng to find a spot. And we managed one, in a far corner, by some teachers. Alan turned to me and said, “You should’ve taken the Press Pass.” I said, “No. I want to be with my family. I want to be with you guys.”

“We would’ve been all right. We’re in a good spot, now.” And I looked at what we’d found as a puwesto. It was close to the VIP section (though still fenced off and far away from the shore). It was in the shade. It was pretty good, at least decently comfortable even if the photos would be too distant to be of use. And then I began to think about it.

“Go back,” Alan said. “Go tell him you changed your mind.”

“No,” I said, afraid to look foolish. “That would be ridiculous. I’d already turned him down.”

“Just ask. Look. We’re all right. See? This is for your work. So, go and do it,” Alan instructed. I looked at my Boy. He mumbled something to his dad like, “Isn’t that the whole point we’re here, for Mama’s work?” I don’t know why, but in that moment it felt like such a hard decision, one that working mothers have to face all the time. When to stay and when to go. I also felt this wonderful sense that it was a good thing, something I’d be proud of that my son could see me at work and see the value of women working, doing things that aren’t strictly traditional.

“All right,” I said and sighed. “I guess I’ll go.” I still felt foolish. “All I can do is ask, right?”

At that very moment — I kid you not — the Man’s assistant showed up with a Press Pass dangling from a string necklace in his hand. He gave it to me and indicated for me to put it on. He waited. OMG! The timing was so brilliant!

I spent the rest of the morning following the Manila and Cebu press folks around. Me, this little writer from Chicago. And, in the end, the Man’s staff let Alan and Boy-boy in to sit with the VIP’s. Was it kindness or guile? Or a practical move? Or all of the above, to get more coverage of the event and spread the publicity? Probably all. And, man, am I thankful.

Kadaugan, Part III: War and Peace

When planning for this trip, I’d focused a lot on the Battle of Mactan. It’s what we Westerners tend to focus on in history: the battles, the wars. I’m not the first (and won’t be the last) to notice that we human beings seem to mark our epochs from one time of war to another. Even the word “Peacetime”, which my elders lived through, means the time after MacArthur, the time after WWII in the Philippines. Peace, often becomes synonymous with an absence of war, rather than a fertile and vibrant time that defines itself. What does the heart of peace look like? What IS actually a creative sense of PEACE? How is it lead from the Spirit?

So, when, a few days ago, I thought that I wouldn’t be able to attend the Re-enactment, it shocked me artistically. It made me realize how much I was depending upon the idea of this battle to define Filipino history. It’s a challenge to feel tossed at sea with no clear sense of the Story. But, like most things, I find that when I surrender to instinct, try and humble down and listen to what life has to teach, ultimately it leads to a deeper place.

When I thought I’d miss the Battle of Mactan Re-enactment, it forced me to rethink would I could see in its absence. And what I saw was this:

* The Santo Ninyo Basillica (still missing the tilde!).

* I saw elder women selling red candles before the open doors of the cathedral.

* I saw people praying for transformations in their lives.

* I saw very poor, hard-working tinderas at the side of the road selling Sto. Ninyos.

* I saw a country, rich in natural beauty, rich in family ties, rich in spirituality even as the politicians may struggle with corruption and a hard economy.

* Songs and dances in praise to God.

* Offerings to Diwata, Nature Spirits.

* Boys with their arms draped around each other in camaraderie.

* Old traditions of babaylans continuing, though much changed, today.

The Elder women here fascinate me. They are small and wiry, bronzed by the sun. Two things are persistent about them: Their powers of negotiation at the market stalls and their smiles, very humble and sincere. Theirs is not the strength of canons, but the enduring strength of palm trees. They are able to bend with the flow of wind current and survive.

Mosquito Scoreboard

In 1983 –> 17 mosquito bites. Mosquitoes declared winners.

In 1994 –> 14+ mosquito bites. Mosquitoes declared winners.

Now, 2007, the rematch:

20 April

Got here yesterday — zero mosquito bites!

Been up and out this morning — zero bites!

21 April – 26 April

After walking and taking jeepney all over Cebu City; being out on the coast; sleeping at Marine Sanctuary in Oslob — 3 mosquito bites.

The East Coast of Cebu

Historical Background:

The challenge of writing about the sixteenth century Philippines, or sixteenth century Britain for that matter, is that so much has changed or been lost to modernity. For countries like my beloved Philippines, there’s the added challenge that history has been vanquished by the soldiers and colonial governments. What I find myself having to do to is re-create that time period by going back to sources like Antonio Pigafetta, Magellan’s chronicler. I have lists and lists of plants, animals, and other things he saw during first contact between sixteenth century Visayans and Magellan. I have taken those lists and brought them with me on this trip. And I’ve tracked down which animals and plants I can. The challenge is tremendously exciting! Of course, it’s difficult to know with complete certainty, for example, if the “black bird” he mentions is a specific one endemic to Cebu (more on that at a later posting).

The work of historians, anthropologists, and religious studies professors has been crucial to my understanding of that time period. Archaelogists have discovered that during the sixteenth century, the port of Cebu was a large and active trading port. Shards of ceramics from China have been found in Cebu City (using stratigraphy to date them) long before Magellan’s landing. Other Chinese shards have been found in towns all along the Eastern coastline of Cebu. It’s believed that the port of Cebu was a distribution point for the rest of the barangay (settlements).

So that’s where I started my own re-creations, the east coast of Cebu. A local environmental organization brokered for me a tour down through several cities and municipalities — all the ones where I’d read there was archaeological evidence of settlements during the sixteenth century. These are quite rural places. Beautiful. Usually municipalities that have just become cities. Most families fish and farm for a living. The men go out in small banca (1-2 people outrigger boats) where they either spear fish or use lines for catch. They return and the women sell the fish in the marketplace. It is a very old tradition, this division of labor.

Action Plan:

To recreate sixteenth century Cebu I tried to be in or around as much nature as I could. I sought out whatever local, endemic animals and plants I could find. And I tried to track down things Pigafetta had described in his chronicles. The caveat is this: No culture, no matter how simple ever stays the same over 500 years. All I could do was go sideways — get a sense from modern Cebuanos of how their resourceful ancestors may have lived from the traditions they still maintain today. Like weaving, fishing, seafaring, and house-building.

I sound all academic in this post. *laugh* But it was tremendous fun to put deep anthropological research in the service of historical fiction! I took a private 2 day tour of the East Coast of Cebu: Naga, Carcar, Talisay, Alcoy, Daliguete, Argao, Boljoon, Oslob. The forest of Alcoy. A protected Marine Sanctuary in Oslob where my family and I, guided by the ever-resourceful Maretes (more on this wonderful woman later), snorkeled and saw Philippine coral reefs for the first time. If there is no such term as Historical Ecology, I’d like to coin it now because I got a chance to see animals that have been around at least for the last 500 years and organizations like the Coastal Conservation Education Foundation are working hard to preserve them.

Here’s an excerpt from my excellent 2 days of researching the East Coast:

Today, I drove w/my family stopping at small cities and barangays on Cebu’s east coast.

Today, I saw a real mangrove w/my own eyes for the first time.

Today, I learned the history of cities like Talisay, Naga, Carcar from a fish warden, an agricultural officer, and a tourism officer.

Today, I saw old photos that were taken of antiques and relics.

Today, I saw how people make tuba (palm wine) from palm sap.

Today, I met women hand-weaving mats and long swatches from abaca (pineapple thread).

Today, I was in the presence of a carabao, a pig, a parrot, and lots of kambing (goats). I saw an enormous balete tree (daket in Cebuano) and the way palm and banana trees stand together.

Today, we saw hermit crabs roam footpaths along the shore.

Today, I learned to recognize the warning of the tuko lizard and heard the siloy sing its sad and beautiful warning song.

It was a good day.

Lagtime, 4/26/07

Before the trip, my plan was to do field research during the day and then spend about half an hour blogging each night to keep in touch with friends and family outside of the Philippines. But, you see, those plans were made before the Advent of Jetlag.

The time difference between Cebu City and Chicago is fifteen hours. That means that, literally, our days and nights are flipped upside-down. The last time I was in Manila, twelve years ago, I landed on an evening flight and slept the entire next day sprawled out on my cousin’s bed. So, I expected the same would happen here. It’s no big deal. You just sleep it off and then adjust to the, albeit huge leap, in time zone.

But every journey’s different and when we landed last Thursday, it was 5:30 a.m. Manila time. We got to the Manila Airport Hotel, our stop-over before heading out to Cebu on Friday afternoon. We were tired, but very, very excited. And wide awake. This was unexpected.

So, instead of sleeping off the day, we called our relatives and met them earlier than anticipated. We crammed Auntie M, Uncle E, Uncle C, Auntie E and our own little family of three into our air-conditioned hotel room and caught up on family stories. It was a great impromptu reunion!

This was the first time Alan and Boy-boy had met any of them. As Alan said later, clearly tickled, “You’re relatives are so cute! Every one of them!†Uncle E has the smooth, deep voice of a radio announcer. He and Auntie M kept making these jokes about getting older. She said, “You always think of yourself as young.†And he adds, “Until – until somebody calls you Tatang.†Which is an affectionate term for elder, or father. “Soon,†said Uncle E, “I will be Lolo (grandfather.) And after that? SUPER Lolo.†I don’t if this translates. Part of the humor is in Uncle E’s delivery.

Filipinos here seem also alternately surprised and amused that Alan can speak Tagalog. They look at him with his blue eyes and pale skin, his beard and American clothes and don’t expect him to say things like, “Magandang umaga! Meron po kayo nang Globe Card?†(Globe is a company that provides calling time on cell phones.) We love seeing people’s reaction at the seeming incongruity. Mostly, it’s fun to mess with people’s expectations.

But anyway, back to the point I was trying to make with this blog entry: Jetlag threw off my blog writing time considerably, which is why I’m having to play catch-up. Here’s an excerpt from my journal: “If you’ve never had jetlag before, it feels something like this – When you’re standing still, the earth sways beneath your feet like a ship’s deck riding a huge swell. Can anyone say queasy?†We felt this way for maybe 4 days. Now, the queasy feeling is gone.

My body had fallen into a rhythm of falling asleep at around 8 or 9 p.m. Cebu City time. I’d wake up at 3 or 4 a.m., read, research, and generally think through my action plan for the upcoming day. Then, I’d get exhausted by 5 a.m. Back to bed for another hour or hour-and-a-half of sleep. Usually, I was wide awake by 6:30 and we’re out to breakfast at around 7 or 7:30.

I’ve learned since our last trip to Greece, that it’s best to follow my body’s rhythm. The jetlag isn’t something you necessarily have to fight. Your body finds its own way of marking time. Waking up at 4 a.m. to work hasn’t been so bad. In fact, it’s the time of day when the entire family is quiet. I’ve been waking up at that time with my thoughts cogent and research questions clear and realizations about the previous day’s work come easily in the tahimik, the peace of early morning.

So, let’s see how many entries I can put online this morning to catch up. It’s 6 a.m. in Cebu City now. To our friends and family in the States: Have a great dinner!

Kadaugan, Part II: Reversals

Life, like the plot of a juicy and unpredictable novel, can have reversals. One afternoon, we were told that the best view of Cebu City would be from the Taoist Temple in Lahug, an affluent part of town in the mountains and home to a thriving Chinese Filipino community. We took a taxi there.

On the radio was a Cebuano talk-show. Now, I can hang out fine in Tagalog, but Cebuano is far beyond me at this point. After about 5 days of being surrounded by this vibrant language, I’ve come to love its rhythm, its dips and dives and fast footsteps. And I notice many words that end in –an or –on.

However, the talk show host was dropping names like Tupas. Then, Lapu-lapu. And, finally, when I heard the name Magellan, I knew that they were talking about the historic event of his landing and subsequent defeat. I pricked up my ears and strained to understand any words at all possible. It’s AMAZING what you can focus yourself to do under the right circumstances.

When we got to the mountains, I told our driver, Jun, that we wanted to see the Kadaugan but that we were told it was already finished. No! he said. He’d just been listening to an hour’s worth of programming. They’d been announcing the Re-enactment and that it was happening (yes, yes, yes!) this Saturday. He gave me the number of the radio station so I could confirm it. What relief I felt at this news I cannot tell you.

What I’ve learned from this is to always check and counter-check the word on the street (any street, any city). The next day, I called the Department of Tourism for final confirmation and *finally* got the official answer and the starting time of the event. Internet is not always reliable or its info complete.

If I had it to do all over again, I would’ve spent the extra $5.00 or whatever it cost to call the Department of Tourism of Cebu from the States to confirm what I’d read about the Kadaugan online – to save these 2 days of grief and uncertainty.

I think it was Julia Cameron, in ARTIST’S WAY, who suggests, “Leave the drama for the page, not for life.â€

Kadaugan, Part I: Word on the Street

Excerpted from private journal, 21 April 2007, 2:45 a.m. Cebu time:

It’s nearly 3 a.m. I’m not sure, but I think I’ve hit a low point in the trip. I’m feeling a bit discouraged. Yesterday, the shuttle driver who picked us up from the Mactan-Cebu International Airport told us that the Kadaugan Re-enactment of the Battle of Mactan had already happened in January or March for the ASEAN Conference. This, I knew about already from following Cebuano news over the last couple of months. But the tourism boards kept showing that the Battle was still going to be re-enacted on the 27th for the local communities. Two other young men I’d talked to had no idea what events were even happening for the Kadaugan.

And then, even worse, the shuttle driver introduced the idea that the Philippine Star and the local radio have been saying that Magellan was really killed in the CAMOTES ISLANDS (where, most notably, I will NOT be staying).

Let’s recap: Word on the street is that there’s no Battle of Mactan Re-enactment this April. And that Magellan was NOT killed in Mactan like the shrine and much of the scholarship I’ve read says. So WHY did I travel thousands of miles to get, literally, half-way around the world to conduct research in April?

I’ve had a monkey-wrench thrown on my grasp of history. And the planned climax of my research trip may not happen.

The Big Three

It’s Thursday the 26th now and I’m trying to remember what happened last Saturday, 21 April, our first full day in Cebu. It was an amazing day. Despite the set-back of the news that the Battle of Mactan Re-enactment was not happening, I forged ahead with my family in tow. They have been incredibly good sports about my dragging them about and being on my research schedule (even when there’s no clear schedule to speak of or things change, suddenly, as they do on journeys).

Writing historical fiction is sometimes like being a bloodhound. You have to sniff out the scent, follow the faint and lingering clues of history. The most obvious places to research are museums, bookstores, libraries, and monuments. Last Saturday, April 21st, we toured Cebu City’s Big 3: The Santo Nino (which sounds like Ninyo when I can get the Spanish tilde to work) Basilica, Magellan’s Cross, and Fort San Pedro.

The Santo Ninyo was a gift given by Magellan to “Queen Juana” (aka Humaymay) after her “baptism”. I put these things in annoying little quotes because, like most really good stories, everything depends on one’s interpretation and viewpoint. The Santo Ninyo is a statue of the Christ Child, or as I like to think of him, Baby Jesus (sounds friendlier and more accessible to me). Fort San Pedro is the earliest Spanish stronghold in Cebu from which the rest of the island was colonized; it was used by the Spanish government for defense. And Magellan’s Cross is a replica of the original one implanted by Ferdinand Magellan on the shores of Cebu.

[This is a very simplified and cursory overview of those historical sites. Mostly ’cause it’s getting late and this blogger is tired!]

What’s hard to explain to anyone who hasn’t visited the Philippines is this incredible sense of spirituality that permeates the air and slides in, under my skin. Yes, perhaps it’s humidity. Or perhaps it’s just the heat. But, no, I am just being flippant — because it really is hard to explain the sincerity and fervor of prayer here. Old women stand in front of the Basilica selling thin, red tapered candles to light when people make petitions to the Christ Child.

One of the things I find amazing is the thought that people humble themselves down to ask for very basic things that we all want: Health. Security. Love. Peace. Food.

Before I left, I had been reading a field guide for historical fiction writers. They say that field research is a very risky thing. Who knows if the book will even sell to recoup the expenses of such a grandiose trip? This is a very practical concern. But my completely impractical take on it is: When else would I have the chance to have a transformational journey like this? To share the history of my heritage with my husband and pass on this knowledge to our son?

But the field guide also said that there’s nothing like experiencing something first hand. Whether it’s following the Oregon Trail by covered wagon or talking to re-enactors about how to card wool. If I could step back in time, I would, just to get Cebu, Mactan and that gorgeous and dangerous time period inside my bones — because, in the end, that’s how we write the most powerful stuff. From the inside out.