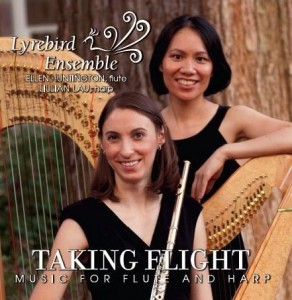

Harpist Lillian Lau and flutist Ellen Huntington are an elegant duo with a mission to reinvigorate interest in music composed specifically for harp and flute. Ellen is an award-winning Instructor of Flute at North Park University, a soloist, chamber musician teacher, and orchestral musician. Lillian is an orchestral musician, educator, solo harpist, and chamber recitalist who has performed with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, the National Repertory Orchestra, at the Grant Park Music Festival, the Ravinia Festival and throughout Europe. Together, they are Lyrebird Ensemble.

Harpist Lillian Lau and flutist Ellen Huntington are an elegant duo with a mission to reinvigorate interest in music composed specifically for harp and flute. Ellen is an award-winning Instructor of Flute at North Park University, a soloist, chamber musician teacher, and orchestral musician. Lillian is an orchestral musician, educator, solo harpist, and chamber recitalist who has performed with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, the National Repertory Orchestra, at the Grant Park Music Festival, the Ravinia Festival and throughout Europe. Together, they are Lyrebird Ensemble.

Lark-song greeting sunrises and sunsets. Wings swooping and gliding on the wind. A pounding Maori waterfall. Cascading rivulets. And water nymphs. Lyrebird Ensemble transports you to riverbank and sky on their debut album Taking Flight. The album is, in turns, playful and soothing. Check out Ellen and Lillian’s interview, music links, and join the Midwest’s celebration of spring’s return!

– Mary Grace

How did you arrive at your duo’s name?

Lillian: Lyrebirds are among Australia’s best-known native birds, most notable for their superb ability to mimic natural and artificial sounds from their environment. They are also known for their striking beauty when the male tail is fanned out in display.

Ellen: The name is appropriate since the lyre is precursor to the harp and birds in music are most often depicted by the flute.

Can you tell us what kind of flute and harp each of you plays?

Ellen: I play a handmade Miyazawa 14 carat gold flute with sterling silver keys. In fact, I am a “Miyazawa Artist”, a representative performer of this flute maker and I am featured on their website. Miyazawa flutes are made in Japan.

Lillian: I play a 47-string concert grand pedal harp made by Lyon & Healy of Chicago, IL. It is made from Birdseye Maple for the body of the instrument, and Sitka Spruce for the soundboard. The seven pedals connected to the mechanism make it possible to play technically challenging music.

Congratulations on your new CD, Taking Flight, Music for Flute and Harp. How did you choose the composers and songs for this album?

Ellen: Most flute and harp duos play a very small selection of repertoire, and a lot of that repertoire consists of transcriptions, or music originally written for other instruments. While I was doing my doctoral studies at Northwestern and deciding on a dissertation topic, I began compiling a list of works written specifically for flute and harp, and came up with over 800! Lillian and I read through over 100, identifying pieces that interested us. This is how we discovered the lesser-known works on the CD, by Bemberg, Grandval and Folprecht, and thought it would be great to record these pieces that most people have never heard. We decided to include the Alwyn and Farr since they are both beautiful and exciting, fit our 20th century theme, and, together with “The Song of the Lark”, gave a nature-inspired theme to the CD.

What does the album title, Taking Flight, mean?

Lillian: When the Lyrebird Ensemble was considering an appropriate album title, we wanted to capture the nature themes from the musical titles. Taking Flight is also a celebration of our debut recording. Hopefully, there will be more to come.

Ellen, can you tell us what role birds play on the Taking Flight CD?

The flute can be heard specifically imitating bird sounds in “The Song of the Lark”. Much of this piece is written without strict meter. In some sections, the harp provides an ostinato background over which the flute plays a free bird-like melody. The composer gives guidelines about the note lengths and phrasing, but the interpretation is mostly left to the performer.

The work by Alwyn was actually inspired by the idea of water nymphs, and the flute and harp often combine to create sounds that are flowing or rippling like water. There are also sections in this piece where the flute plays a soaring melody or some fast trills that could be reminiscent of bird sounds.

Lillian, on Charles Rochester Young’s “Flight” from The Song of the Lark, you create an exciting sound – a rhythm – that seems unusual for a harp. How did you create that sound?

Lillian: The composer gave specific instructions to weave a narrow piece of paper through the strings. When I pluck the strings, the paper partially dampens the strings’ vibration, thus creating the unusual sound effect. Several modern pieces on the CD, “The Song of the Lark”, “Naiades”, and “Taheke”, use complex rhythms which create excitement. I played percussion before becoming a professional harpist so rhythm is something very familiar and percussionists are constantly creating new sounds from existing instruments.

Twentieth-century composers William Alwyn and Gareth Farr wrote songs inspired by the River Blyth in Britain and Huka Falls and the Waikato River in New Zealand. How do harp and flute play off of each other to create the sensation of water movement?

Lillian: The harp features two common techniques that evoke the sound and movement of water: the arpeggio, multiple notes playing in sequences over the 7 octaves of the harp and the glissando, a glide over a range of strings.

Ellen: The combination of constant arpeggios or a steady series of eighth notes or sixteenth notes in the harp creates a very relaxing backdrop for both of these composers’ long, lyrical melodies for the flute. I often picture a very peaceful scene of gently flowing water while I play these sections of music.

Where do you go to reconnect with nature?

Ellen: I love the peacefulness of the ocean when I am able to travel to the beach. I also love the wide-open vistas of the Southwest, specifically New Mexico and Arizona. I traveled to Arizona last May and spent time hiking near Sedona, and visiting the beautiful Grand Canyon and Monument Valley.

Lillian: One of my favorite places is the Colorado mountains. I spent a summer there making music and playing concerts outdoors. Ever since we chose the title Taking Flight I frequently notice flocks of birds taking flight in the sky.

Is there anything special Lyrebird Ensemble would like readers to know about your music?

Lillian: We will continue to discover new music and bring something unusual that the audience has not heard before.

Thanks, Lyrebird Ensemble for your excellent musical offerings and taking us on another artful excursion into nature!

You can hear more of Lyrebird Ensemble on Live from WFMT, the signature live performance series of Chicago’s classical radio station.

Photos and music samples courtesy of Lyrebird Ensemble. www.lyrebirdensemble.com